Parks are on sacred lands

For thousands of years, these lands have held the stories of indigenous nations. That legacy still shapes how we walk, learn, and belong here.

Every step you take in a national park is on ancestral homelands.

Long before the U.S. government claimed these spaces as “federal lands,” indigenous peoples lived, traveled, and thrived here. The National Park System—like the nation itself—rests on land taken during colonization, often through violence, broken treaties, and forced removal.

The weight of that truth is real—and indigenous nations are still here.

Communities that survived this trauma carry forward cultures, languages, and environmental knowledge that span millennia. Their presence is not just historical. It’s active. It’s enduring. And it matters.

Today, we’re part of the next chapter.

The National Park Service is working more collaboratively with tribal nations to honor their sovereignty, cultural stories, and sustainable stewardship. And as visitors, we can listen, learn, and show up differently—starting with how we walk the land.

“What is this you call property? It cannot be the earth for the land is our mother… How can one man say it belongs only to him?”

Ousamequin (c. 1581 – 1661), sachem (leader) of the Wampanoag confederacy, also known as Massasoit (Great Sachem).

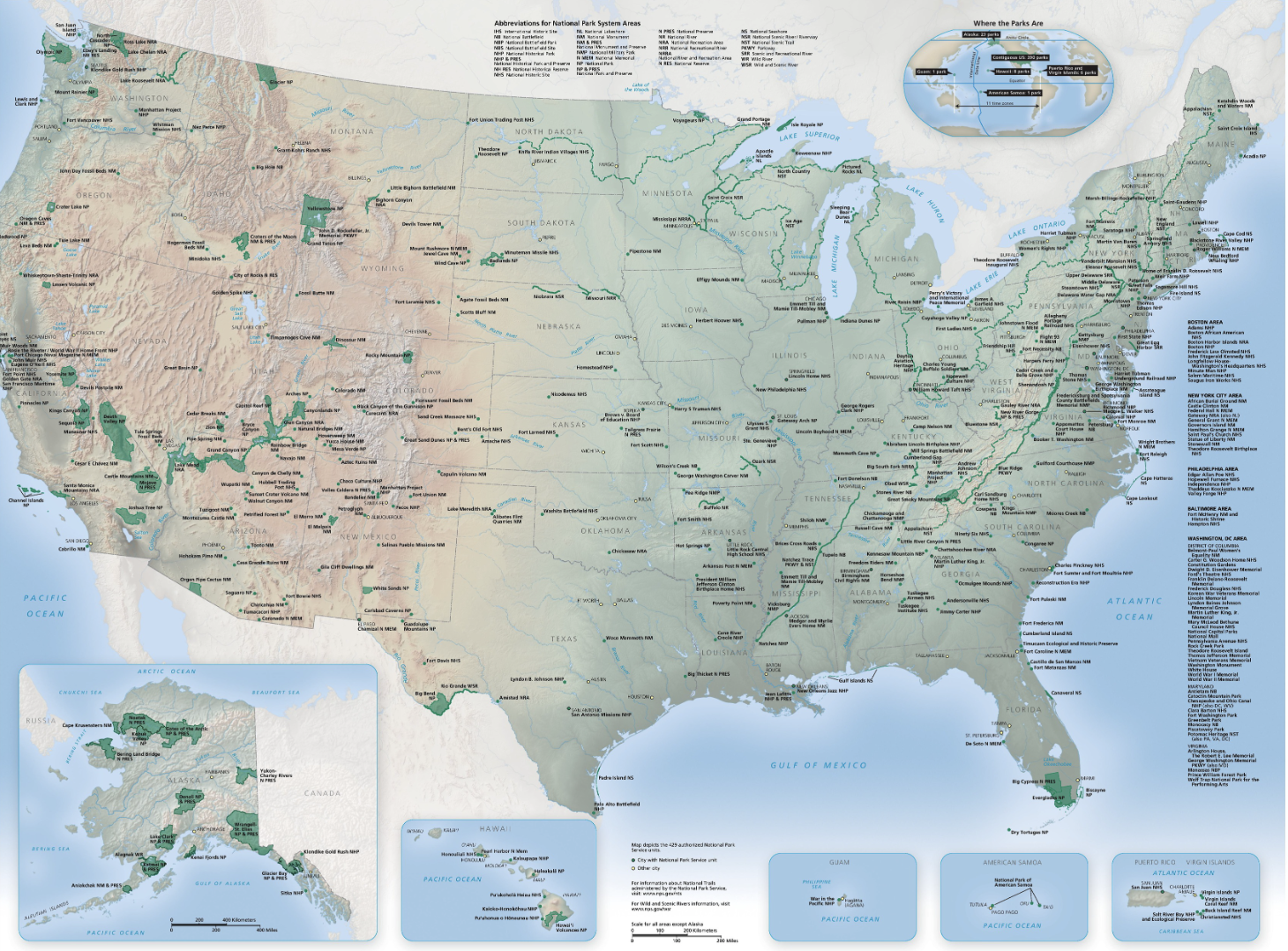

A brief history of U.S. National Parks on Indigenous Homelands

Whose land are you visiting? Knowing is a first step. Respecting is the next:

Advocates and Educators

-

INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS (IWGIA)

-

U.S. NATIONAL PARKS SYSTEM

-

NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS (NCAI)

This page is a living invitation.

We know that land acknowledgments are only a beginning. As we continue to learn, we welcome guidance, corrections, and connections from indigenous educators, creators, and community members.

Have something to share? Reach out through our contact form.